УРАЛЬСКОЕ ОТДЕЛЕНИЕ

РОССИЙСКАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК УРАЛЬСКОЕ ОТДЕЛЕНИЕ ИНСТИТУТ ХИМИИ TBEPДОГО ТЕЛА |

|

|

| 30.05.2007 |

|

|

|

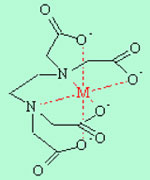

Adding cheap chelated iron supplements to cereals could help beat childhood iron-deficiency anaemia, a major malnutritional condition in the developing world. Pauline Andang'o and colleagues at the Kenya Medical Research Institute and Wageningen University, the Netherlands, report large reductions in iron-deficiency anaemia among Kenyan school children fed maize-flour porridge fortified with chelated iron. Their results are published in The Lancet. Iron-deficiency anaemia affects around half the developing world's children. Their mainly cereal-based diets contain high proportions of phytic acid, whose six phosphate groups make it a strong chelator of nutritionally important minerals, including iron, calcium, and zinc. Lacking the ruminant enzyme phytase, humans cannot digest phytic acid, so sequestered minerals pass unabsorbed through the gastrointestinal tract. Some flours are fortified with finely ground iron powder, said Ted Greiner, senior nutritionist at the Washington-based international non-profit health organisation PATH (Program for Appropriate Technology in Health), '[but] it alters the flour's colour, taste, and shelf life, and doesn't ensure iron's bioavailability'. Non-chelated iron is insoluble above pH 3.5, so it precipitates in the small intestine, impeding efficient absorption. 'Iron deficiency is widespread, difficult to treat in low-income settings, and gets little attention,' Greiner said. 'Andang'o and her colleagues have a solution.'

Iron chelated to ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) survives the stomach's low pH (like phytic acid-bound iron) but is steadily released and absorbed in the higher pH small intestine. The joint team tested maize flour fortified with EDTA-chelated iron in a randomised trial on four groups totalling over 500 Kenyan school children, between the ages of three and eight. Each group ate the same daily amount of maize-flour porridge five times a week. The placebo group's porridge was unfortified, while two groups' were fortified respectively with high- and low-dose EDTA-chelated iron: the last group's porridge was fortified with electrolytically-produced iron powder. Those on high-dose EDTA-chelated iron had the greatest reduction in iron-deficiency anaemia (89 per cent) compared to the low-dose group (48 per cent), with no reduction for those on electrolytic iron. 'If we'd extended the five-month test period, reductions in iron-deficiency anaemia would have been even greater. But we need to do more work to determine the safe dose of EDTA', Andang'o warns. Though it can improve dietary zinc absorption, EDTA could also induce zinc deficiency. Greiner is more sanguine however, calling for mandatory fortification of all processed cereals. Lionel Milgrom

References P E A Andang'o et al. Lancet, 2007, 369, 1799

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|