Chemists in China have coated living cells with egg-like shells, granting them a wide range of new properties. These 'super cells' not only have an extended lifetime but are impervious to enzyme attacks, and can even be made magnetic. The findings could lead to new methods for preserving and transporting useful cells such as stem cells, say Ruikang Tang and colleagues at Zhejiang University, Hangzhou.

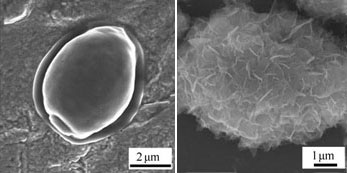

By mimicking the way nature makes eggshells, the team completely encased cells of baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a layer of calcium phosphate. 'We first attached carboxyl-rich polymers to the cell walls, which act as mineralisation inducers,' Tang explains. 'These negatively-charged groups are able to capture calcium phosphate from a supersaturated solution, depositing them onto the surface of the cell and building up a shell-like layer.'

The resulting mineral coating - only a few hundred nanometres thick - is stable in water and air, and immune to attack from zymolyase, an enzyme that dissolves the cell walls of yeast cells. The team was also able to incorporate nanoparticles of magnetite (Fe3O4) into the mineral shell - causing it to become magnetic.

A baker's yeast cell, before (left) and after (right) its eggshell armour is added

© Angewandte Chemie

|

Importantly, the cell inside remains healthy and can survive for weeks longer than unprotected cells. This is because can enter a 'resting state' and can survive despite being completely sealed with no access to normal nutrients. To release the cells when they are required, the shell can easily be dissolved by ultrasound or using a weak acid.

Tang believes that this kind of coating could find a wide range of applications. 'We think that this could be used to build shells around useful cells, such as osteoblasts [which build new bone], and then transport them to where they are needed using functional shells as the vehicle,' he told Chemistry World.

'Protecting cells in an inorganic suit of armour is a nice idea and has important implications for cell storage and collection,' says Stephen Mann, a specialist in biomineralisation at the University of Bristol. This kind of process could also find uses in encapsulating stem cells or moving DNA between cells, he adds.

Lewis Brindley

Enjoy this story? Spread the word using the 'tools' menu on the left.